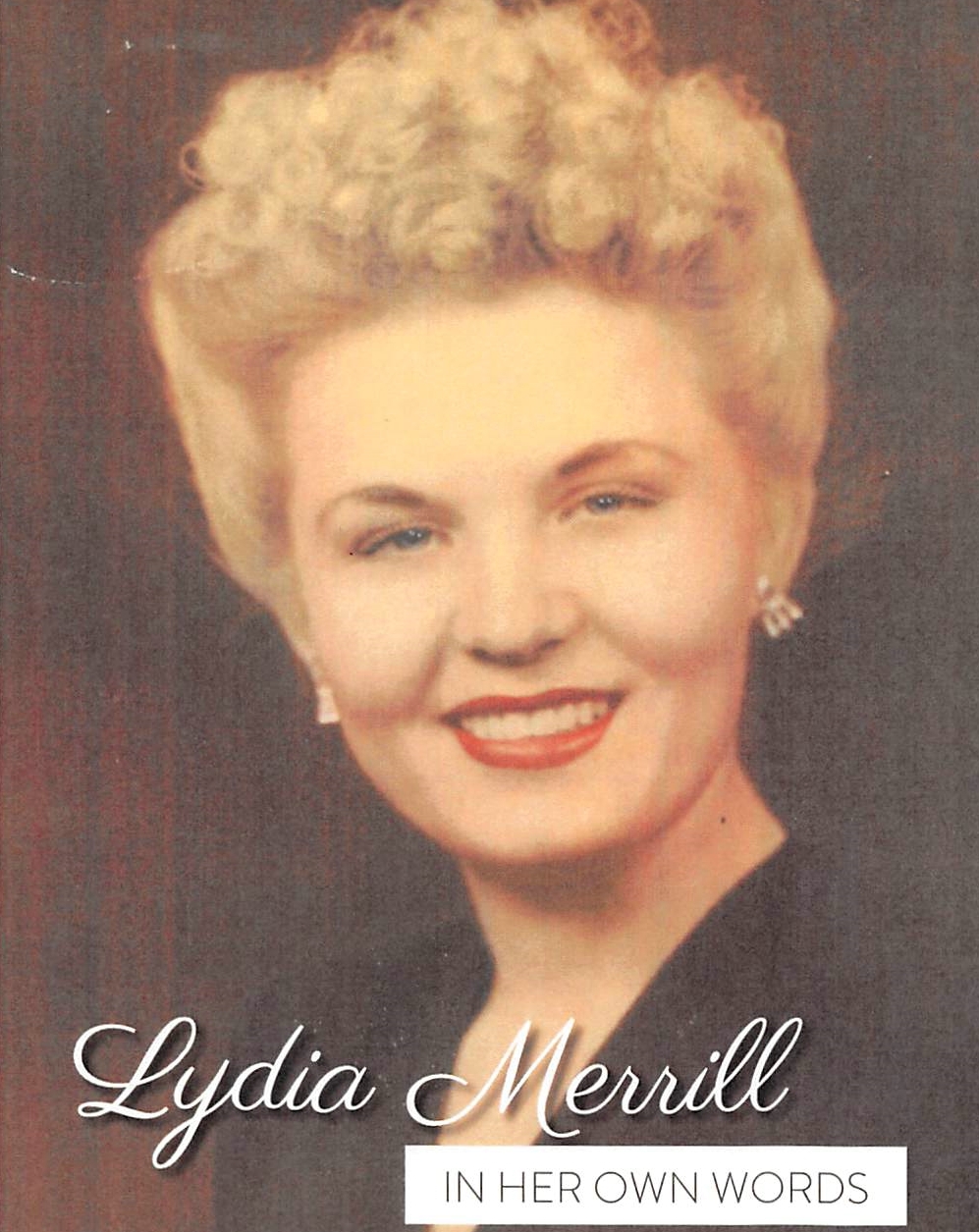

Obituary of Lydia Helmuth Merrill

In Her Own Words

Lydia has always been adorable from the time she was first held in the arms of her parents, Sophie and George Helmuth, on August 18, 1915, in Fresno, California.

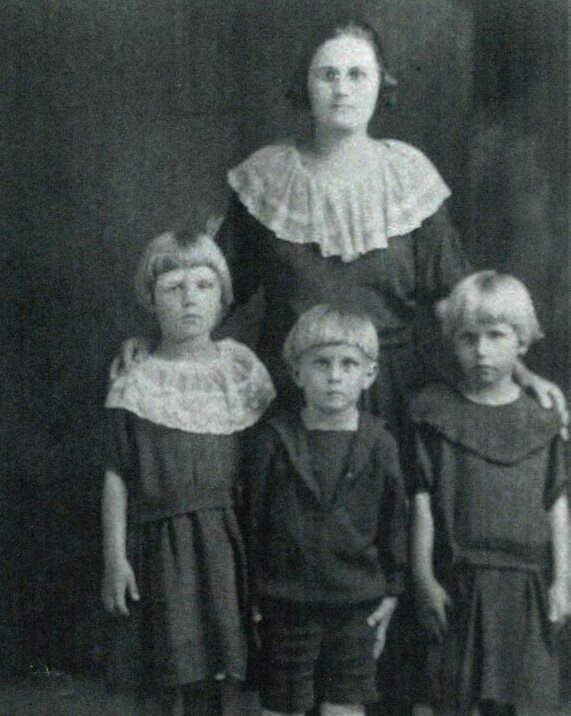

George and Sophie were German immigrants from the Volga River region in Russia who settled in “German Town,” an area of Fresno, California, home to fellow immigrants fleeing from religious persecution in Russia. George was just 19 when he married, so he was a young father. “My father was quiet and thoughtful,” Lydia recalls. “He was a family man. He bought me an encyclopedia and a player piano before I was four. He was an elevator operator and died in an elevator accident when I was five. I remember the funeral and I knew it was serious.”

Life changed for Sophie, Lydia, and her younger siblings, Alvina and little George. “My father provided the family with life insurance, which helped us a lot. My mother began working in a fruit packing house.”

“Sophie,” Lydia remembers, “was timid and mostly quiet. I never heard her raise her voice in anger. We lived a quiet life. We did not have a radio or telephone. We did not have a car. We walked wherever we wanted to go; almost everyone we knew did, too. Our life centered around our church, the Church of God. We went to church often. My friends were there, we sang and played music together. We celebrated holidays there. I learned how to play the piano and violin because the minister’s wife encouraged me. I still remember my best friends, Elsie Schmidt, Elma and Alvira Roth.”

Lydia was asked, “If you were to return to your youth, what would you do differently?” “I went to church, I met my friends, I played music and sang with them. I wouldn’t want anything to be different.”

Lydia played the violin in her high school orchestra and had this story to tell: “One spring day our orchestra was invited to play in the park. After the program I wanted to join my friends so I put my violin under a tree thinking it would be safe until I came back. When I returned it was gone and was never found. I was so upset that I never played again.”

What was Lydia like as a young girl? “I was timid and did not take risks. I didn’t try things. I didn’t do out-of-the-ordinary scary things. I never wanted to ride a bicycle or learn to swim. I was afraid of the water. I was always cautious and I have never broken a bone. I was always afraid of getting lost so I was never lost. The darkness scared me. Whenever I went outside the house there were no lights or cars. It was just dark.”

“I liked school and liked to study. I never played hooky. Math (algebra and geometry) was my favorite subject, but not English. When I was in grammar school I wanted to be a German teacher, but I thought my talents were playing the piano and the violin. Best of all I liked to read. I would rather read than do chores. I would rather read than wash dishes. Sometimes my sister would complain about me.” What was the naughtiest thing you remember doing and were there consequences? She replied, “I was too timid to do anything naughty but that doesn’t mean I didn’t think of doing something naughty.”

When Lydia was asked to relate her happiest memory as a youth, she said, “I always felt like normal happy.” Lydia seems to have a gift of being naturally happy. Her cheerfulness is heard today in the smile of her voice as she says “Hello.”

Lydia’s life changed again when she was fourteen. “My mother had been a widow for nine years. She had suitors, but had not encouraged anyone. It was the Schmidts at church,” Lydia recalls, “who thought that my mother would make the perfect wife to reform an alcoholic brother who did not go to church. His name was Karl and they were married.

Karl turned out to be a mean drinker who liked to scare people. He rented a farm so he was not at home that much but when he was there we were terrified.”

“I left home because of the conflict. Now, when I think about it, I am amazed that I was so young, but managed to find jobs to put myself through school. Mostly I was a live-in housekeeper. I had a room and board plus $5 or $10 a month. One couple I worked for were elderly. The wife was sickly and I just did what needed to be done. I was like a daughter to them.”

How did Lydia dress as a teenager, and did she go to parties, did she have boyfriends? “I wore mostly dresses to the knees or longer, my hair was not long or short, but medium. Hats? Not very often. No jewelry. The church did not believe in jewelry or makeup. I was an adult before I ever wore makeup.

“Sometimes I went with friends for picnics in the mountains. Sometimes my friends had parties in their parents’ homes. We didn’t listen to music but would just eat and talk.”

“I had a lot of boyfriends. When I was seventeen I especially liked one boy, Johnny Granter. I knew him from church. He had a nice personality and he was popylar with everyone, but he began to like my girlfriend better than he liked me. I felt bad. It’s odd,” Lydia added, “at the time things happen it’s a big deal. You feel sad or whatever kind of emotion, then years later it’s hard to even remember.” Johnny Granger later married Lydia’s girlfriend.

After graduating from high school Lydia desperately wanted to attend college, but with no funds available, she settled on business school and became qualified as a secretary. “I learned shorthand but wasn’t very good at it. I did love typing and could type 75 words a minute for 15 minutes. I worked as a secretary after graduating and rented an apartment with a girlfriend. I had a phone for the first time. You had to talk to the operator who would connect you to other numbers. Wages were cheap, but bread cost 5 or 10 cents, meat 10 or 25 cents a pound and real estate, $13,000 for a property. I didn’t see much of the world,information was scarce and my interests were mostly about my personal life.”

It was dancing that Lydia loved as a young woman. “Dancing was the most important thing. I wore dressy dresses, not casual. Blacks were the style of the day, but I liked color and I liked glamour.” Both Lydia and her roommate were busy with work, boyfriends, and dancing every weekend. Sometime during Lydia’s studies at business school, Lydia was asked by a fellow student if she wanted to double date a man who worked with the fellow student’s girlfriend. His name was Orson. What was Lydia’s first impression of Orson? “He was handsome but he didn’t kiss me on the first date. He thought he was being polite, I think. That politeness impressed me.”

Lydia continued dating and going to dances. For some reason Orson didn’t share her interest in dancing, but offered to take Lydia to dances and even offered to take her home if she did not have a ride. Orson graduated from cosmetology school so he would fix Lydia’s hair before she went to the dances. It would seem Orson was smitten, adored Lydia, and was just going to be polite. Their relationship took a turn, however, when Lydia realized how much Orson cared for her. As she tells it, “A young man who worked at the drugstore asked me to go to a movie I wanted to see. I didn’t think anything of it. It seemed innocent at the time, so I said ‘yes.’ When we were in line I saw Orson was in line, too. He saw us and became very upset. He was jealous. I had never seen him so upset.”

How did Orson propose? “It was not a one time thing. It was over a period of time. We knew each other for about a year. After six months he wanted to get married and kept talking about it. I just didn’t say much. Orson just kept asking and talking (about it).” Finally, Orson tried the one thing that worked. “Let’s go to Reno,” he said, and on November 7, 1937, they were married in Reno, Nevada. “We didn’t want crowds, we didn’t want relatives or friends, we wanted something simple, nothing fancy or elaborate. We found a witness off the street and were married by the Justice of the Peace. Our honeymoon and wedding were one. After spending the night in Reno we returned the next day and went to work. Orson picked up a hitchhiker on the way home, so it took a little longer.”

What is the best thing you have done in your life, Lydia? “Marrying Orson, he is the best thing life.” Those of us who witnessed their

65-year marriage and life-long love affair can affirm that it is a rare and wonderful gift they shared.

Many years have passed. Orson left his adorable Lydia in 2003, but she joined him on November 6, 2021.

COMMENTARY

The Idaho Statesman • Sunday, August 16, 2015 • IdahoStatesman.com

CELEBRATING 100 YEARS AT THE MARDI GRAS

Anyone who knows Lydia Merrill knows she isn’t one to blather on about herself. She wanted this to be about the Mardi Gras Ballroom that has been such an important part of her life—not about her.

Fine, it will be about the Mardi Gras.

And, with due respect, about Lydia. It can’t not be about her and her late husband, Orson Merrill. They and their stories are as much a part of the Mardi Gras as its hard-rock maple dance floor.

To say nothing of the fact that Lydia is celebrating her 100th birthday and tonight her family and friends are throwing her a birthday bash in the old ballroom.

The Mardi Gras, for newcomers and others who may not be familiar with it, was a Boise institution long before many of today’s Boiseans were born.

It opened in 1928 as the Riverside Pavillion, an open-air dance hall near the intersection of Ninth and River streets.

Bootleggers did a thriving business there during Prohibition. Gib Hochstrasser, who went on to become a local institution as the leader of an iconic big band, made a nuisance of himself in his youth by climbing the perimeter walls to watch the orchestras he idolized.

Until the cops ran him off.

Orson Merrill, a high-school dropout, erstwhile hobo and successful beautician, bought the dance hall (by then it had a roof) on impulse in 1958.

“His insurance agent said, ‘Why don’t you buy the old Riverside?’” Lydia recalled. “Orson said, ‘OK. I know it’s big. I’ll buy it.’”

His reasoning was that the ballroom was big enough to attract large, admission-paying crowds. It took a while to happen, but in time the crowds would exceed his wildest imaginings.

Dancing wasn’t initially what he had in mind. Orson loved to pick up hitchhikers. (He drove one miles out of their way on his and Lydia’s wedding night.) When he picked up an airman hitchhik- ing from Mountain Home to the military skating rink at Gowen Field, he figured that if people went that far to skate, a roller rink in Downtown Boise would be a money maker.

“He went out and bought a bunch of skates and we had a skating rink,” Lydia said.

Skating didn’t prove to be as popular as he thought, so he returned to the original formula.

“He started having dance music again,” their son, Tim Merrill, said. “He got a band called Manny and the Crystals. Many would slide across the stage and play the guitar with his teeth. (This was nearly a decade before such behavior was popularized by Jimi Hendrix.) Dad set them up with sound equipment in exchange for getting Manny’s pistol in trade.”

Orson was nothing if not colorful. When a college student who was sitting on one of the tables next to the dance floor refused to move, Orson stuck him with a hat pin. Mistakenly thinking it was his, he used a nail to scratch his name onto a band member’s expensive microphone. He was known to stop the music during a dance to clean spills off his beloved dance floor, which he installed himself. He also dug the ballroom’s basement.

With a shovel.

The Merrills changed the name from the Riverside Ballroom to the Uptown Ballroom and ultimately to the Mardi Gras, Lydia said, “because Mardi Gras meant fun.”

No argument. Musicians who played there during the Merrills’ heyday included Buddy Rich (who praised its acoustics on the Tonight Show), John Lee Hooker, Pinetop Perkins, Willie Dixon, Albert Collins, the Ventures, Paul Revere and the Raiders, Leon Russell and Edgar Winter, Johnny Winter, David Lindley, R.E.M….

I was there the night Buddy Guy played for 1,200 people, packed elbow to elbow.

“Bobby Vee played there on my 15th birthday,” Lana McCullough, Lydia’s daughter, said. “He wanted to dance with me, but I was too shy.”

The Basques used to have their annual Sheepherders Balls there.

“We had sheep in here,” Lydia said, wincing.

These days the Mardi Gras is best known for ethnic dances, square dances, swing dances, parties and the occasional rock or blues show.

And, of course, Lydia—an institution in her own right. While Orson was busy digging the basement, fussing over the dance floor and being generally colorful, Lydia’s was the quiet presence and cool hand that helped keep the place running, especially following his death in 2003.

At 100, she has no intention of retiring.

“She works in the office, and she’s here every Sunday vacuum- ing and washing tables,” McCullough said. “There’s nowhere else she’d rather be.”

“And I like being at the dances,” Lydia added. “I love seeing people having a good time on our dance floor.

“…I’ve only been in the hospital once. I told the doctor if I made it to 100 I’d go for 110. And who knows? I feel good, and I still enjoy spending time in this old place. I just might make it to 110.”

Tim Woodward

LOCAL

The Idaho Statesman • Monday, April 14, 2003 • IdahoStatesman.com

THE GIFT OF DANCE

I heard with great regret that Orson Merrill of the Mardi Gras Ballroom passed on. also, I remember with much joy and deep appreciation all that he gave to this community.

Orson and his Mardi Gras gave us first-class entertainment, where a lot of us as young adults learned to become better, more socialized individuals. We came together as young adults to socialize and to appreciate culture in a warm and classy environment that cannot be bought with money, only with love and understanding of your fellow man. He gave Boise a format for culture and artistic expression that truly did reach around the world. He gave the young and the old, anybody who wanted to have a great night with other awesome members of our society a medium where we could all join together.

But most of all, because of his love of life, he gave us the opportunity to really dance like it was the best thing that people of all kinds—young, old, black, white—could be doing together. He was social grace in action. I’d like to thank the Merrills for sharing so much with all of us.

Cindy Edmonds, Boise

To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Lydia Merrill, please visit Tribute Store